There is a problem that most indie musicians like me encounter very soon. You finish mixing and mastering a new song, import it in your favorite music player and - shock - when you listen to it, it is way quieter than songs by your favorite artists. Maybe even quieter in such a way that you have to raise the volume to 100% whereas you listen to other songs at just 20%. Frustrated because of the ruined listening experience, you go back into your DAW and by making extensive use of dynamic-range compression, limiters and other maximization tools, you try to push your loudness to it’s limits, sacrificing as many dynamics as you can bear, in order to compensate.

Enter the world of the so called “Loudness War”. This phenomenon began escalating in the 90s when artists noticed that their songs on compilations were quieter than others. As a result, the loudness was increased which led to other artists increasing their loudness even more. I think you can imagine what happened: The loudness of songs kind of exploded over the last few decades.

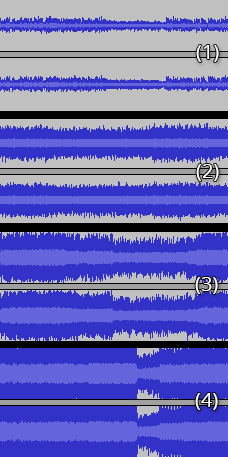

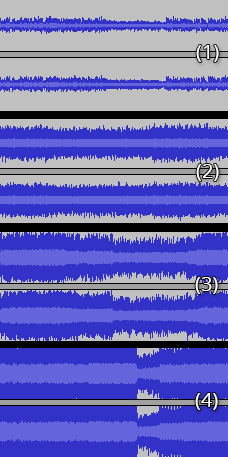

Let’s have a look at an example. I recently finished working on a new song and encountered the problem again. I imported several songs in Audacity and compared their waveforms. In the screenshot, you can see excerpts from (top to bottom)

- (1) my song (which is normalized according to EBU R128, more about that later),

- (2) The Sisters of Mercy’s “Temple of Love (1992)”,

- (3) “Élan” from Nightwish’s new album “Endless Forms Most Beautiful” and

- (4) “Du und ich” from the German band In Extremo’s album “Kunstraub”.

As you can see, all of them look pretty different. My song (1) has a relatively low volume with much space for dynamic range. Temple of Love (2) is louder but still has a little bit of space left. Élan (3) is very close to the 0 dB border and sometimes limited. There is no space left and compression seems to be a compromise of loudness and quality. Finally, Du und ich (4) is reaching 0 dB almost all the time. Obviously, heavy compression and limiters were used as the song has no dynamic range left most of the time.

Many songs, especially in the Rock/Metal genre, look like the last one, nowadays. Thus, the loudness war is heavily criticized because sound quality is always lost and the overall listening experience not as enjoyable as it could be. Of course, loud songs can still be great songs and sometimes the loss of dynamics is not very noticeable, but then there are professional mastering engineers who have a lot of experience and money for doing just that. However, an independent musician like me has no chance to achieve comparable loudness for a small budget without a huge impact on quality.

But enough complaining about the dilemma. What can we actually do about it? I think the war is still far from being won, but there are technologies and recommendations that, I believe, are huge steps in the struggle to end it.

One of those is the recommendation R128 by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Since radio stations had the problem of normalizing their content to a constant average loudness and different radio stations tended to have different loudness, such a recommendation was necessary and became widely used in 2012. It is based on the international recommendation ITU-R BS.1770 which specifies a standard to measure loudness. If you have a compliant loudness meter (like the open source LUFSMeter which is what I have been using), you can measure the overall loudness of your song. EBU R128 recommends to normalize a “programme” to -23 ± 0.5 LUFS (Loudness Units relative to Full Scale). I followed that recommendation with my new song. As you can see in (1) the -23 LUFS target loudness is surprisingly quiet, but therefore the specification allows a dynamic range up to -1 dB.

“Okay, so radio stations normalize their content to -23 LUFS”, you may think, “but why should you? There will still be the problem with the loudness difference in my iTunes playlist!” Well, not really because there is more to it. The key is loudness normalization technologies that you can use too. Two are worth mentioning right now: iTunes Sound Check and ReplayGain. As you can guess from the name, the former is used in iTunes and can be enabled in the playback preferences. The latter is an open source alternative that more and more players (e.g. foobar2000 and Winamp) support. Basically, both do the same. They measure the loudness of your music files and store a volume gain value in the tags. When playing, that gain is applied and songs in your playlist will sound equally loud. Additionally, they support the so-called album mode which applies the gain relative to the overall album loudness. This stops loudness differences when listening to a whole album and respects the original behavior.

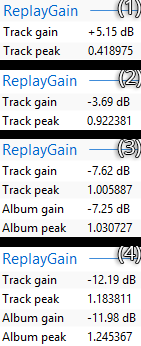

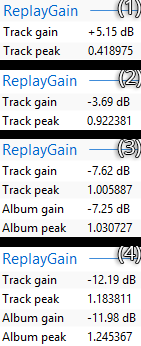

In the second screenshot, you can see which gain values ReplayGain in foobar2000 stored for the four songs we looked at earlier. My song got a boost by about 5 dB, but all of the other ones actually have reduced volume. (3) and (4) have a peak over 1 and are reduced by quite a lot.

So, why do I think loudness normalization is awesome? As you can see, you can still compress the hell out of your music, but with tools like iTunes Sound Check and ReplayGain, it won’t matter anymore. You will sacrifice dynamics for loudness and, in the end, have your volume reduced by the player. A song like mine, however, still has all of the dynamics and sounds equally loud.

I don’t know what the future will come up with, but for now, I’m confident that we are on the right track. I think I will normalize my next album in compliance with EBU R128, hope that more and more people use loudness normalization tools and break it down to this:

People probably prefer a good song over a loud one.